In this post we’ll take a look at “Turgenev’s Maid”; a type of female character typical for Turgenev and often found in his novellas and novels.

Nicolae Grigorescu, A Flower Among Flowers, 1880

Nicolae Grigorescu, A Flower Among Flowers, 1880

Although equally important for Russian Realism, Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev is often overlooked when it comes to Russian writers, somewhat overshadowed by the more famous Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy. Out of those three writers, Turgenev was the one influenced by the progressive ideas and philosophy of Western Europe and even spent majority of his life in France where he died too. His mother was a tyrannical woman and his parents’ marriage an unhappy one, so Turgenev decided to stay a bachelor. There’s elegance in his writings and an emphasis on nature and its lyric beauty. There’s nothing dramatic about his writing, but somehow it lingers in the memory and you find yourself pondering over some things that meant very little the moment you were reading it. Also, his words leave some kind of quiet sadness and a sense of futility against life, love and nature. Can you stop the flower from withering, sun from setting, springs from lingering one after another and passing?

Turgenev’s first novel was “Rudin”, first published in 1856 in a literary magazine “Sovremennik” (“The Contemporary”). In this novel, he laid a foundation for his future characters and themes by introducing a female type of heroine which came to be called “Turgenev’s Maid” and a hero who is a young superfluous man. Turgenev is continuing and developing the types of characters that Pushkin had started in his novel “Eugene Onegin”. Characters follow the similar pattern in his novella “Asya”, published in 1858. Turgenev’s odes to failure in love.

Photo by Frieda Rike.

A typical Turgenev’s maiden is a girl whose introverted, reserved, modest and shy exterior hides a passionate and poetic soul that only few people see, but is hidden to the rest. She is romantic and dreamy, but not in a delusional Emma Bovary kind of way, but rather this romantic nature arises from idealism and life spent in the idyllic countryside isolation which can sometimes make her inexperienced in society. She is educated, both in history and geography as in daydreaming, and often speaks several languages. She possesses a gentle, girlish, unassuming beauty and is modest in behaviour and the way she dresses. Turgenev’s maiden often falls in love with man unworthy of her; weak and passive idealists who are excellent in conversation but incapable of doing something with their life. As I already said, Turgenev’s heroines draw heavily on Pushkin’s wonderful Tatyana Larina from “Eugene Onegin” and here is what D.S. Mirsky says about it in his discussion about Turgenev: “The strong, pure, passionate, and virtuous woman, opposed to the weak, potentially generous, but ineffective and ultimately shallow man, was introduced in literature by Pushkin, and recurs again and again in the work of the realists, but nowhere more insistently than in Turgenev’s.”

William Powell Firth

Natalya Alexyevna Lasunskaya

Natalys is a shy seventeen year old girl who lives in the countryside with her mother. On the outside she seems reserved, very secretive and cold, but that is just her way of hiding her feelings from the world and her dominant mother. She is introduced in the story in the fifth chapter with these words: “Darya Mihailovna’s daughter, Natalya Alexyevna, at a first glance might fail to please. She had not yet had time to develop; she was thin, and dark, and stooped slightly. But her features were fine and regular, though too large for a girl of seventeen. Specially beautiful was her pure, smooth forehead above fine eyebrows, which seemed broken in the middle. She spoke little, but listened to others, and fixed her eyes on them as though she were forming her own conclusions. She would often stand with listless hands, motionless and deep in thought; her face at such moments showed that her mind was at work within.”

But further quotes reveal to us that Natalya’s feelings are strong and that her mother doesn’t understand her personality at all: “But Natalya was not absent-minded; on the contrary, she studied diligently; she read and worked eagerly. Her feelings were strong and deep, but reserved; even as a child she seldom cried, and now she seldom even sighed and only grew slightly pale when anything distressed her.”

Heinrich Vogeler, Spring (Portrait of Martha Vogeler), 1897

Life in the beautiful countryside amongst family friends has made her inexperienced with the ways of the world and she is a perfect pray for Rudin, a poor intellectual unsure of what he wants from life or love, indulging himself in shallow melancholy and praising highly the courageous heroes of literature and history while he himself is beneath them, both in spirit and intellect. He takes a pleasure in seducing Natalya because his feelings aren’t as deep or as pure as hers are, and since he had many failed loves in the past, he doesn’t take the relationships seriously. For him, it’s just a past time, but in Natalya he has awoken a whole new set of feelings, ones that she only read about in literature. After Natalya admits her love for Rudin to her mother, and is met with mother’s disapproval, she meets Rudin secretly at the brake of dawn somewhere in the meadow to tell him the sad truth, expecting him to fight for their love.

Marie Antoinette (2006)

This is their poignant, sad and bitter dialogue from chapter IX:

“‘What do you think we must do now?’

‘What we must do?’ replied Rudin; ‘of course submit.’

‘Submit,’ repeated Natalya slowly, and her lips turned white.

‘Submit to destiny,’ continued Rudin. ‘What is to be done? I know very well how bitter it is, how painful, how unendurable. But consider yourself, Natalya Alexyevna; I am poor. It is true I could work; but even if I were a rich man, could you bear a violent separation from your family, your mother’s anger? . . . No, Natalya Alexyevna; it is useless even to think of it. It is clear it was not fated for us to live together, and the happiness of which I dreamed is not for me!’

All at once Natalya hid her face in her hands and began to weep. Rudin went up to her.”

What you have just read is a typical Turgenev-style ending; the heroine is too passionate and her feelings too strong for the passive hero. It’s not that Rudin doesn’t love Natalya, it’s more that he is incapable of being himself, living his own life, to commit to someone. Once rejected, Natalya doesn’t go on daydreaming of Rudin or returning to him. Instead, just like Pushkin’s Tatyana, she walks away with dignity and self-respect.

William Dyce, Portrait of Princess Victoria, the eldest daughter of Queen Victoria and Albert, 1848

Asya

In “Asya”, the narrator, a lonely forty year-old bachelor named N.N. tells us the sad love story of his youth. His memory sets the novella in a small and picturesque town on the Rhine, whose shore is littered with romantic Medieval castles and emerald green hills; a perfect setting for a fleeting, ephemeral romance. The narrator comes there on a holiday and meets two fellow Russians, a brother and a sister; Gaguine and Asya. Since they are the only Russians in town, they soon befriend. The narrator develops an intellectual bond with Gaguine but is soon enamoured by his strange and pretty younger sister Asya who is very shy around him at first.

This is what Turgenev tells us of their first encounter: “My presence appeared to embarrass her; but Gaguine said to her, “don’t be shy; he will not bite you.” These words made her smile, and a few moments after she spoke to me without the least embarrassment. She did not remain quiet a moment. Hardly was she seated than she arose, ran towards the house, and reappeared again, singing in a low voice; often she laughed, and her laugh had something strange about it—one would say that it was not provoked by anything that was said, but by some thoughts that were passing through her mind. Her large eyes looked one in the face openly, with boldness, but at times she half closed her eyelids, and her looks became suddenly deep and caressing.”

And this is how Turgenev imagined her to look like. Again, she has a very girly appeal, just like Natalya and other Turgenev’s maidens: “The young girl whom he called his sister at first sight appeared to me charming. There was an expression quite peculiar, piquant and pretty at times, upon her round and slightly brown face; her nose was small and slender, her cheeks chubby as a child’s, her eyes black and clear. Though well proportioned, her figure had not yet entirely developed.”

Photo by by SophieKoryn. “You consider my behaviour improper,” her face seemed to say; “all the same, I know you’re admiring me.” (Asya)

Asya can be rapturous and wild at one moment, without any regard for social conventions, only to become shy the next moment, wistful and lost in her thoughts. Here is an example to illustrate the point: on one occasion, Asya breaks a branch from a tree and plays with it as if it was a gun. When they encounter a group of shocked English tourists, she starts singing in a loud voice just to spite them. But later in the evening, she is the epitome of elegance and demureness: “When we arrived, she immediately went to her room, and did not reappear until dinner, decked out in her finest dress, her hair dressed with care, wearing a tight-fitting bodice, and gloves on her hands. At table she sat with dignity, scarcely tasted anything, and drank only water. It was evident she wished to play a new rôle in my presence: that of a young person, modest and well-bred. Gaguine did not restrain her; you could see that it was his custom to contradict her in nothing. From time to time he contented himself with looking at me, faintly shrugging his shoulders, and his kindly eye seemed to say: “She is but a child; be indulgent.”

Jenna Coleman as Queen Victoria in “Victoria” (2016)

Here is a little conversation from the ninth chapter which also reveals Asya’s lack of feeling for proper behavior:

“And what is it that you like about women?” she asked, turning her head with a childlike curiosity.

“What a singular question!” I cried.

“I shouldn’t have asked you such a question, should I? Forgive me; I am accustomed to say whatever comes into my head. That is why I am afraid to speak.”

“Speak, I beg you! Fear nothing, I am so delighted at seeing you less wild.”

Juliette Lamet by Melanie Rodriguez for Melle Ninon.

The narrator seems more interested in the mysterious aura around her, than actually in love with her, he says himself: “Oh! that little girl—she is, indeed, an enigma.”

Here are a few more quotes to get you interested:

“I understood what attracted me towards this strange young girl: it was not only the half-savage charm bestowed upon her lovely and graceful young figure, it was also her soul that captivated me.”

“I do not know what womanly charm suddenly appeared upon her girlish face. Long afterwards the charm of her slender figure still lingered about my hand; for a long time I felt her quick breathing near me, and I dreamed of her dark eyes, motionless and half closed, with her face animated, though pale, about which waved the curls of her sweet hair.” (Chapter IX)

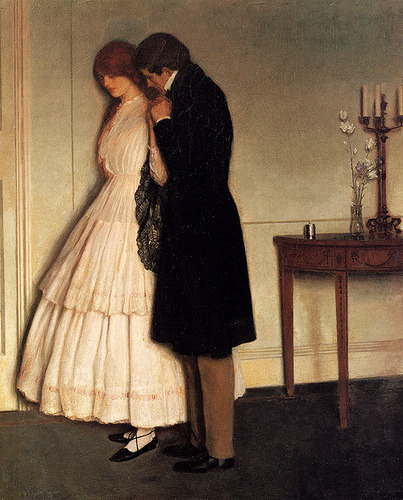

William Powell Frith, The Proposal, 1856

The end of their love, again the hero suddenly turns cold and steps back from the affections that he himself started in the first place:

“So all is at an end,” I replied once more; “at an end—; and we must part.”

“There was in my heart,” I continued, “a feeling just springing up, which, if you had left it to time, would have developed! You have yourself broken the bond that united us; you have failed to put confidence in me.” (chapter XVI)

To end the post I would like to quote a fellow blogger at “A Russian Affair” who focuses on Russian literature. Here are her brilliant observations on Turgenev’s themes and style from the post “Typically Turgenev“:”Not a lot happens in Turgenev’s works. The situation at the beginning is more or less the same as the one in the end. All that remains is memories and what-ifs. The reader has to content himself with plenty of beautiful atmospheric scenes and contemplations. (…) You read Turgenev with your heart.”

And a beautifully put thought regarding love from her post “Love in Turgenev’s work“: “It all starts in high spirits; the weather is ’magnificent’ and ’unusually good for the time of the year’ and the surroundings are idyllic. The sudden appearance of an exceptionally pretty girl surprises the narrator. He falls in love, but he never gets the girl, and remains a bachelor. Again and again Turgenev describes being in love, but he never dares to let it blossom into a relationship, nor in his stories, nor in real life.”

I hope you decide to read some of Turgenev’s work, if you still haven’t and that you enjoy it as much as I did.

Thank you so much for mentioning me on your wonderful blog! I enjoyed reading your vision on the Turgenev’s maiden, and as it happens I just started writing another Turgenev post, long overdue! As you say so well, his writing is very elegant and lingers in your memory. Turgenev is hugely underestimated outside of Russia, perhaps exactly because at first sight there’s not much that happens in his work. I’m always happy to hear from fellow Turgenev lovers and promoters!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for reading my blog! It’s always a pleasure to read about Turgenev and Russian writers, especially when someone’s writing style is as interesting, to the point, and inspires me to read more. I am so looking forward to your next post about Turgenev! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

And I’m looking forward to your future posts! 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

Never read Turgenev,and after your highly informative post I feel I don’t have to.Are they all “Beautiful young girl is left broken-hearted by weak insipid man”? Sounds like Pushkin Lite,but I’m prolly wrong.

It’s raining here and I just counted eight vintage velvet jackets in my wardrobe.Yeah eight! Seems strange?

Bach cello music,and early Carter Family.Best A.

LikeLiked by 1 person

For the past few months I’ve read a lot of Turgenev’s works and was enchanted. I was never much of a fan of Russian literature, I guess because of the cultural clash, but Turgenev instantly struck me as different. I felt that I could love him, and I did. He writes some of the best heroines of all time. It’s rare that I can find women in books that I can relate to so much, that it feels like a little bit of your soul is there. And that’s the thing with Turgenev’s girls, I think: they don’t need intellect, though they’re naturally intelligent, they’re all soul. Their gentleness and refinement are innate. Everything is natural and delicate, it wasn’t moulded by anyone, not even by the girls themselves. I can’t explain myself well, but I truly loved getting to know many of his works and being introduced to such special, relatable young women.

Even his bad women are incredibly written: they chill my blood. I think they border on the sociopathic. Yet he writes them so delicately, it’s never violently obvious that they’re evil, although they very much are.

For the sake of curiosity, which books and heroines are your favourites? My favourite books are On The Eve, House of the Gentry, Asya, Smoke and First Love, and my favourite heroines Yelena, Lizaveta, Natalya (from Rudin), Gemma (from Spring Torrents – though the latter two are not my favourite books of his) and Vera (from A Month in the Country). I’m also weirdly fascinated by Irina from Smoke, although she’s one of his bad women. But she’s so well written. Turgenev really understood the feminine psyche, perhaps because he was such a gentle, kind man himself, more feminine than masculine, I think.

And oh dear, I rambled way too much. Sorry!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree with everything you said! I love his female characters immensely, they are so inspiring and have inner richness. I love Asya and Natalya too, though Rudin angers me hehe. The men in the novels are never fit to be with the marvelouse heroines.

LikeLike

I forgot to mention his men, I really dislike them too, I try not to and be compassionate, but I can’t help it. 😛 They all tend to be weak-willed, easily led, irresponsible and verbose, but never accomplish anything they brag about.

LikeLike

Hahaha. So true!

LikeLike

I would advocate for Turgenev’s originality from Pushkin and other contemporaries. Turgenev’s romantic characters were one side of his writing, but his social commentary was influential and ground-breaking, particularly in “Fathers and Sons” and Sketches from a Hunter’s Album,” which was reportedly influential in the Czar’s decision to end serfdom. Rather than directly emulating Pushkin’s “superfluous men” and female character types, Turgenev may simply be another perspective on sociological archetypes that were prevalent at the time, due to societal forces. The fraying feudal Czarist system, economic stagnation and constraints on career opportunities, in addition to the social restrictions around women’s lives, may have caused Pushkin and Turgenev (and Checkhov) to develop such characters in their works in response to finding models for them in their society.

LikeLike